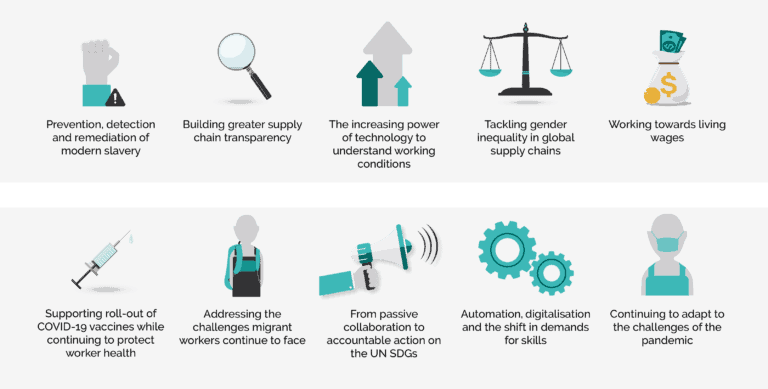

10 priorities for sourcing more responsibly during COVID-19 recovery

After a disruptive 2020, companies increasingly recognise the importance of responsible sourcing to protect business operations and workers – throughout the ongoing pandemic and into a recovery period. So where should businesses seeking to operate more responsibly focus their efforts?

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent disruption has increased awareness of global supply chains and the impacts business decisions can have on workers around the world. The turbulence highlights how supply chain workers are at risk of many human rights issues that are heightened during a crisis, particularly for those already more vulnerable.

This comes at a time when consumers, investors and governments are already reviewing the role of business in combatting human rights and environmental risks. Modern slavery and due diligence legislation, climate targets and trends toward ethical investing indicate the growing focus – alongside businesses themselves looking to operate more ethically for long-term sustainability.

So where should you focus your efforts in 2021? We outline the priorities and considerations for companies looking to source more responsibly this year – whether you’re just beginning your responsible sourcing journey or aiming for best practice throughout every tier of your supply chain.

1. Prevention, detection and remediation of modern slavery

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the risk of modern slavery, while simultaneously making it harder to identify people in forced labour and for victims to access support.[i] The risks to already-vulnerable groups, such as migrant workers and informal workers, will continue to increase as the impact of COVID-19 is felt.[ii] Businesses should prioritise understanding the risk of modern slavery in their own supply chain and taking action to mitigate any impacts on people once these are identified.

This year, the EU looks to introduce a new law requiring companies to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence – which may include companies based outside of the EU who want to operate or sell within it. The UK will also strengthen its existing Modern Slavery Act, including introducing financial penalties. Ultimately, 2021 will see increasing demands for businesses to show how they assess and address the risk of modern slavery, and protect people working in their supply chains.

Sedex recommends: Use a risk assessment tool to understand where there is a risk of forced labour in your business’s supply chain. This will help to identify the regions or sectors with the greatest risk, where further assessment, prevention and remediation efforts are needed most.

We suggest gathering further information about the people working in these areas through a supplier questionnaire, and assess the likelihood and severity of risks present. Develop clear plans to mitigate identified risks and remediate workers if and when cases of modern slavery are identified.

2. Building greater supply chain transparency

2020 demonstrated that it is more important than ever to know your supply chain.

Beyond COVID-19 and the need to ensure functional supply chains during times of disruption, stakeholders are demanding ever greater transparency from companies on how they address human rights and environmental risks. Businesses are expected to know where their products or services are produced, by whom, and under what conditions, and to make some of this information publicly available to back up ethical commitments. This is only possible if a business has a thorough understanding of their supply chain.

Sedex recommends: Map your supply chain – beyond tier one (i.e. beyond your direct suppliers). Aim to understand where components and then the raw materials of your products or services originate, and keep a close eye on the risk of undeclared subcontracting. Risk of worker exploitation can increase the further down the supply chain you go.

3. The increasing power of technology to understand working conditions

The pandemic has disrupted business due diligence processes, which often rely on in-person audits and site visits to assess working conditions. Technology-based tools can support companies to assess their supply chains even with safety restrictions and lockdowns in place. These remain invaluable in 2021 as these restrictions continue to exist.

Sedex recommends: Identify where technology-based tools can support assessment efforts. These can complement other activities such as audits and self-reported information to gather further insight on working conditions. This helps businesses to continue assessing and preventing human rights risks in their supply chains.

4. Tackling gender inequality in global supply chains

The gender poverty gap is expected to rise due to the pandemic.[iii] Many industries hardest hit by restrictions, such as garment and foodservice sectors, are characterised by a largely female workforce. Women are more likely to be in insecure working arrangements[iv]. Women are also more likely to be on the frontline of COVID-19 care, representing 70% of health and social care workers globally.[v] Therefore women tend to be hardest hit financially and, in care sectors, have higher risk of exposure to the virus.

With growing gender inequalities, there is greater pressure on companies to have gender-sensitive strategies for the recovery period and beyond.

Sedex recommends: Gather information on the situations and needs of women in your business and supply chain. Consider what data you capture from suppliers and whether it is split by gender. Set data-informed gender equality targets to inform your strategy and measure progress – from starting to collect gender-separated data to practical action that can be taken to improve gender equality in your business and supply chain.

5. Working towards living wages

In 2021, the number of people in extreme poverty globally because of the pandemic is estimated to be between 143 and 163 million people. This is in addition to the 588.4 million people already projected to be living in extreme poverty this year, based on pre-COVID-19 estimates. [vi] People on poverty wages are unable to save, making them more vulnerable in a crisis that has seen millions lose their jobs.[vii]

The need for a living wage – an income that covers living costs plus some savings – is clear. 2021 will see growing expectations for companies to commit and actively work towards living wages throughout their supply chains – an expectation that some businesses already recognise. In January Unilever announced that they are aiming to pay a living wage to everyone that directly provides goods and services to their company by 2030.

Sedex recommends: Understand the gap between wages paid to workers and local living wages in your supply chain. You can use the IDH Salary Matrix to collect wage information and measure the gap between received wages and a living wage. Once you have an idea of the income gap, begin discussions with your suppliers to identify ways to improve the wages paid to workers. This may include ensuring that the price paid for goods and services covers the cost of a living wage.

6. Supporting the global roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines with stable supply chains, while continuing to protect worker health

As the vaccine roll-out gets underway, it can place additional stress on global supply chains. 2020 stretched personal protective equipment (PPE) provision, bringing risks to workers at both ends of the supply chain. Frontline care workers reported inadequate PPE [viii], while rubber glove factories subjected workers to forced overtime.[ix]

Pressure is now on the vaccine supply chain – raw materials, the production process, packaging, transport, and vaccinators. Pfizer cutting its production target by 50% in December 2020 is an early sign of the consequences that this pressure can have.[x] Getting the vaccine to those in lower-income countries, particularly in rural areas with challenging health infrastructure and logistics, is another key concern[xi] – highlighting the importance of supply chain stability and continuity in protecting public health.

Sedex recommends: Businesses should continue to protect and support workers, and consider where they can support the roll-out and access to vaccines including locally within their supply chain. For example, Tesco subsidiary Best Food Logistics offered its cold chain logistics services to support distribution of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines in the UK.

Collaboration between businesses and local government is essential – both to deliver vaccines and to ensure this doesn’t come at the expense of workers’ rights.

7. Addressing the challenges that migrant workers continue to face

Migrant workers are an inherently vulnerable group, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these vulnerabilities. 2021 will continue to heighten the risks they face.

Migrant workers are far from families and personal support networks, may face language and cultural barriers, and often do not have access to the social protections available to local populations. Lockdown measures, border closures and loss of work have been particularly challenging for this group – with some migrants struggling to return home after losing their jobs[xii].

Migrant workers also play a significant role in essential sectors. Healthcare and cleaning jobs, where workers care for those suffering from the virus and prevent it from spreading further, have a high representation of migrant workers. Sectors such as agriculture have a heavy reliance on migrant workers during peak seasons.

Sedex recommends: It is crucial to understand where migrant workers are employed in your supply chain and the impact of COVID-19 on them. For example, look at the state programmes and supplier provisions in place to support workers – what can migrant workers access? Consider working collaboratively with other businesses in your supply chain to support affected migrant workers. Supply chains and workers that were protected during the pandemic are better placed to recover faster.

8. From passive collaboration to accountable action on the UN Sustainable Development Goals

With less than 10 years to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 2021 sees renewed pressure on business to evidence and be accountable for their actions. The pandemic has brought additional urgency to the SDGs and key elements such as the need for decent work and fair wages, alongside tackling environmental degradation and climate change.

The World Benchmarking Alliance has launched the Social Transformation Framework, which will assess 2,000 companies on their contribution to the SDGs. We also see sector-specific industry collaborations, such as The Industry We Want, seek to hold companies to account on commitments to targets and standards.

Sedex recommends: Take the time to review your strategy, operations, and goals. Look at what targets your company can set to support the SDGs, or the progress made against existing ones. Every business can take steps to promote decent work, drive environmental sustainability, and reduce inequalities.

9. Automation, digitalisation and the shift in demands for skills

COVID-19 has accelerated the shift in business towards more automation and digitalisation. This creates a polarisation of job prospects; while jobs are replaced by automation on the one hand, there is increased demand for digital skills on the other.[xiii]

This trend was occurring before 2020, but has accelerated in the past year. Adaptation strategies are important as changes, including loss of work for workers, can be sudden. The impact is disproportionately felt by workers in construction and manufacturing sectors [xiv] characterised by low wages and high use of temporary contracts.

In the face of significant change within the job market, a considered approach to upskilling and retraining workers will help businesses make the most of their workforces and support future business needs. This will also help to reduce unemployment and financial impacts for affected workers.

Sedex recommends: Businesses should consider the impact of more automation and digitalisation on workers. Identify opportunities for moving people to new roles within a company, or look at developing re-training programmes to help workers develop in-demand skills.

10. Continuing to adapt to the disruption of the pandemic

Operational disruption, lockdowns and other barriers to trade as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to be part of businesses’ realities.

The pandemic has not had an equal impact across the world, both in economic[xv] and human terms[xvi]). Small to medium supplier companies battle against business closures, particularly in the hospitality and non-essential retail sectors[xvii].

Businesses that remain functioning must adapt to maintain their operations, negotiating workforce shortages or surpluses, fluctuating order patterns and disrupted supporting services like logistics. They must also protect workers’ health and limit the spread of the virus. Our latest research explores how supplier businesses are responding to these changing circumstances, from switching up their product mixes and sales channels to providing financial support for workers.

Sedex recommends: Working in partnership with suppliers, helping them to manage the impacts of COVID-19 and protect their business and workers, is key to recovery. This also helps to ensure resilient supply chains – see our recommendations here.

Consider collaborating with trade bodies, governments, peers within sectors/geographies, or other stakeholders to share expertise and access support.

Learn about how to assess the impact of COVID-19 in your supply chain

Contact Sedex to discuss how we can help your business source more responsibly

[i] A. Trautrims et al. (2020) https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/beacons-of-excellence/rights-lab/resources/academic-publications/2020/trautrims-et-al-managing-modern-slavery-risks-in-supply-chains-during-covid-19.pdf

[ii] ILO (2020) https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—ipec/documents/publication/wcms_757247.pdf

[iii] UN Women (2020) https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5142

[iv] https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743623.pdf

[v] UN Women (2020) https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs=5142

[vi] World Bank (2020) https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty-looking-back-2020-and-outlook-2021

[vii] Clean Clothes campaign (2020) https://cleanclothes.org/news/2020/garment-workers-on-poverty-pay-are-left-without-billions-of-their-wages-during-pandemic

[viii] The MJ (2020) https://www.themj.co.uk/PPE-supply-for-care-workers-was-inadequate/219219

[ix] The Guardian (2020) https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/dec/09/nhs-rubber-gloves-made-in-malaysian-factories-accused-of-forced-labour

[x] Reuters (2020) https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-health-coronavirus-pfizer-vaccine/pfizer-says-supply-chain-challenges-contributed-to-slashed-target-for-covid-19-vaccine-doses-in-2020-idUKKBN28D3BH?edition-redirect=uk

[xi] Control Risks (2020) https://www.controlrisks.com/our-thinking/insights/supply-chains-to-be-tested-when-covid-19-vaccine-arrives

[xii] https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/21/migrant-workers-stranded-russia-flocking-border

[xiii] OECD (2020) https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/a0361fec-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/a0361fec-en

[xiv] OECD (2020) https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/a0361fec-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/a0361fec-en

[xv] Our World in Data (2020) https://ourworldindata.org/covid-health-economy

[xvi] McKinsey (2020) https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Risk/Our%20Insights/COVID%2019%20Implications%20for%20business/2020%20updates/COVID%2019%20Nov%2011/COVID-19-Facts-and-Insights-Oct-30-Final.pdf?shouldIndex=false

[xvii] https://www.cips.org/supply-management/news/2021/january/foodservice-suppliers-on-a-cliff-edge-due-to-lockdown/